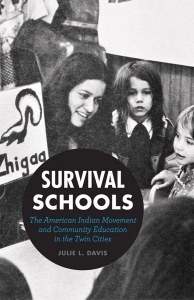

Survival Schools

The American Indian Movement and Community Education in the Twin Cities

Julie L. Davis

The first history of two alternative schools founded by AIM in the Twin Cities in 1972—and their role in revitalizing Native culture and community

In 1972, motivated by prejudice in the child welfare system and hostility in the public schools, AIM organizers and local Native parents started their own community school. The story of these schools, unfolding through the voices of activists, teachers, and families, is also a history of AIM’s founding and community organizing—and evidence of its long-term effect on Indian people’s lives.

"For the first time, Julie L. Davis gives us an essential view of one of the American Indian Movement’s most audacious and long-lasting achievements: the creation of schools for the lost Native kids of Minneapolis and St. Paul. Sympathetic but never sentimental, she captures the righteous anger, new-found hope, and rugged determination that turned dreams into reality."—Paul Chaat Smith, author of Everything You Know about Indians Is Wrong

In the late 1960s, Indian families in Minneapolis and St. Paul were under siege. Clyde Bellecourt remembers, “We were losing our children during this time; juvenile courts were sweeping our children up, and they were fostering them out, and sometimes whole families were being broken up.” In 1972, motivated by prejudice in the child welfare system and hostility in the public schools, American Indian Movement (AIM) organizers and local Native parents came together to start their own community school. For Pat Bellanger, it was about cultural survival. Though established in a moment of crisis, the school fulfilled a goal that she had worked toward for years: to create an educational system that would enable Native children “never to forget who they were.”

While AIM is best known for its national protests and political demands, the survival schools foreground the movement’s local and regional engagement with issues of language, culture, spirituality, and identity. In telling of the evolution and impact of the Heart of the Earth school in Minneapolis and the Red School House in St. Paul, Julie L. Davis explains how the survival schools emerged out of AIM’s local activism in education, child welfare, and juvenile justice and its efforts to achieve self-determination over urban Indian institutions. The schools provided informal, supportive, culturally relevant learning environments for students who had struggled in the public schools. Survival school classes, for example, were often conducted with students and instructors seated together in a circle, which signified the concept of mutual human respect. Davis reveals how the survival schools contributed to the global movement for Indigenous decolonization as they helped Indian youth and their families to reclaim their cultural identities and build a distinctive Native community.

The story of these schools, unfolding here through the voices of activists, teachers, parents, and students, is also an in-depth history of AIM’s founding and early community organizing in the Twin Cities—and evidence of its long-term effect on Indian peoples’ lives.

$22.95 paper ISBN 978-0-8166-7429-9

$69.00 cloth ISBN 978-0-8166-7428-2

336 pages, 42 b&w photos, 5 1/2 x 8 1/2, July 2013

Julie L. Davis is associate professor of history at the College of St. Benedict and St. John’s University in central Minnesota.

For the first time, Julie L. Davis gives us an essential view of one of the American Indian Movement’s most audacious and long-lasting achievements: the creation of schools for the lost Native kids of Minneapolis and St. Paul. Sympathetic but never sentimental, she captures the righteous anger, new-found hope, and rugged determination that turned dreams into reality.

Paul Chaat Smith, author of Everything You Know about Indians Is Wrong

Survival Schools is without doubt a major contribution to the history of American Indian education, but more broadly it sharpens our understandings of women’s work, children, urbanization, and Indian community life in the twentieth century.

Brenda Child, author of Holding Our World Together: Ojibwe Women and the Survival of Community

Evenhanded and engaging in its treatment of a politically charged topic, Davis’s book is highly recommended for academic libraries.

Library Journal

Copiously illustrated and annotated, Davis’ book brings to life an important facet of education in our cities’ recent histories.

Community Reporter

Well written and exhaustively researched, Survival Schools adds a vital new perspective on a transformative moment in American Indian history.

Journal of American History

The book does what few focused historical works do really well: it provides a studied but approachable context for the movement’s shifts in government policy, tribal politics, and social pressure. Scholars will find Survival Schools one of the most useful works written to date on AIM because of its strength in providing both historical context and reliable research.

American Historical Review

Educators today still need to continue to learn this same lesson - to hear and to understand these experiences of disenfranchisement - and it is through books such as Survival Schools that such dialogue and reflection can begin.

Canadian Journal of Native Studies

A tremendous addition to the scholarship on the American Indian Movement.

American Indian Quarterly

Davis. . . offers a refreshing portrait of an oft-maligned organization. Survival Schools will no doubt change the discourse on AIM and Native activism for students of modern American Indian history and education.

Tribal College Journal

Contents

Preface

Introduction. Not Just a Bunch of Radicals: A History of the Survival Schools

1. The Origins of the Twin Cities Indian Community and the American Indian Movement

2. Keeping Ourselves Together: Education, Child Welfare, and AIM’s Advocacy for Indian Families, 1968–1972

3. From One World to Another: Creating Alternative Indian Schools

4. Building Our Own Communities: Survival School Curriculum, 1972–1982

5. Conflict, Adaptation, Continuity, and Closure, 1982–2008

6. The Meanings of Survival School Education: Identity, Self-Determination, and Decolonization

Conclusion. The Global Importance of Indigenous Education

Acknowledgments

Bibliography

Index

UMP blog - Telling true stories about the past

In the last years of her life, a conversation with my grandmother inevitably led to her asking me, "So how is The Book coming?" Each time, the question filled me with love and anxiety—love for her unflagging support, anxiety because usually, it wasn't going all that well. Since it was only was a Ph.D. project at the time, calling it a "book," out loud and in capital letters, also seemed presumptuous. "It's just a dissertation," I would insist.

About This Book

Related Publications

Related News & Events

Julie Davis, author of SURVIVAL SCHOOLS, interviews with Laura Waterman Wittstock on First Person Radio.

Six UMP books on the MN Book Awards Finalists list

Six UMP books on the MN Book Awards Finalists list

Finalists include Larry Haeg, Sue Leaf, Rachael Hanel, Sarah Stonich, Julie Davis, and Penny Petersen.